This is an article published by Kieran Davies, Chief Macro Strategist, on Livewire recently.

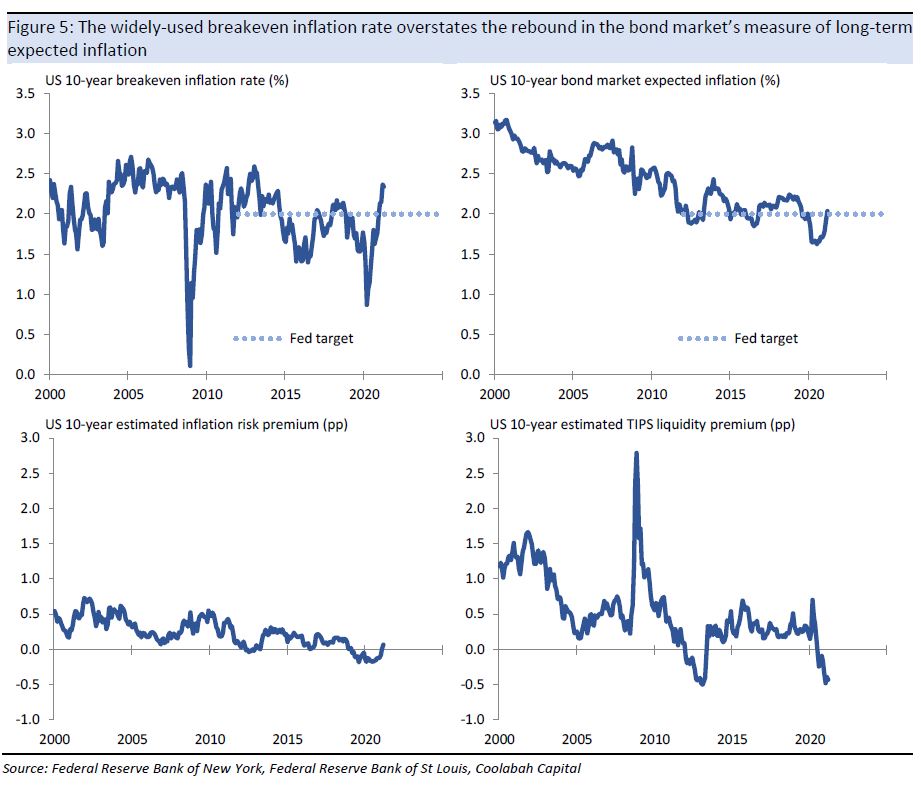

Key former policy-makers and academics have raised concerns about US inflation risks stemming from an unprecedented peacetime stimulus delivered as the economy is recovering rapidly. However, overheating seems unlikely in the short term, with Fed forecasts suggesting it will take until 2023 for the recovery to use up the substantial slack in the economy and with the stimulus peaking in 2021. Inflation expectations are solidly anchored by a credible Fed, with the recent spike in the widely-watched breakeven inflation rate significantly overstating the rebound in the bond market’s expectation of long-term inflation. That said, history shows instances of sudden shifts in expected inflation in response to higher actual inflation. If expected inflation became unmoored and fed into higher ongoing inflation, modelling suggests it would trigger sharply higher interest rates and sharply lower stock prices.

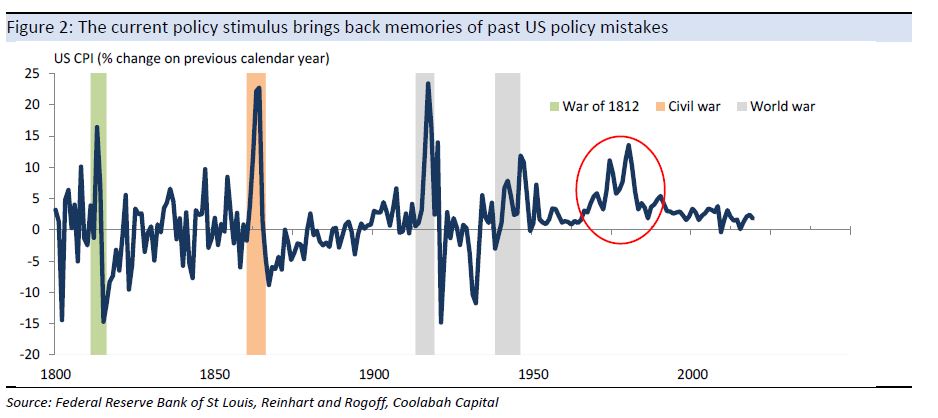

A key former policy-maker has raised concern that US stimulus could drive inflation higher. Earlier this year, former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers penned an influential opinion piece for the Washington Post, which discussed the Biden administration’s $US1.9tr stimulus package that was approved by Congress last month. Summers raised the risk that, “while there are enormous uncertainties, there is a chance that macroeconomic stimulus on a scale closer to World War II levels than normal recession levels will set off inflationary pressures of a kind we have not seen in a generation”. Judging “stimulus measures of the magnitude contemplated steps into the unknown”, Summers worried about the “risk of inflation expectations rising sharply” given the “commitments the Fed has made, administration officials’ dismissal of even the possibility of inflation, and the difficulties in mobilising congressional support for tax increases or spending cuts.”

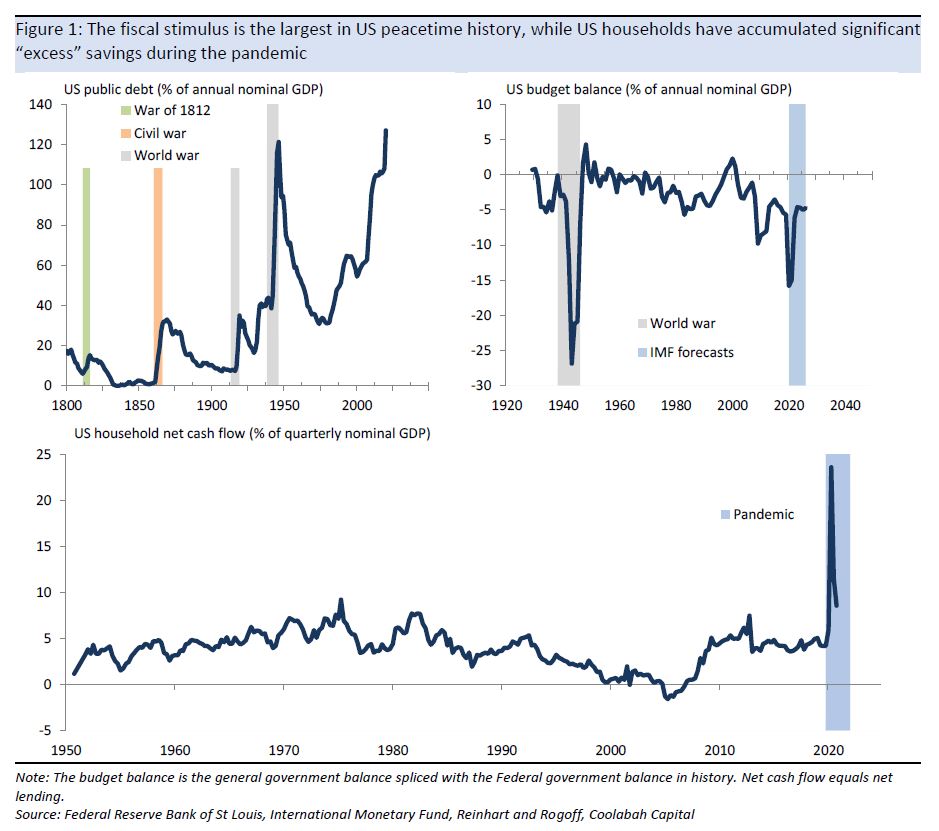

The US fiscal stimulus – combined with “excess” household savings accumulated during the pandemic – totals over 20% of GDP. The US fiscal stimulus is enormous in scope, with the $US1.9tr stimulus that Summers wrote about equating to almost 9% of GDP. It builds on the $0.9tr stimulus delivered late last year, which itself equated to about 4% of GDP. The Biden administration is planning further infrastructure-focused fiscal stimulus reportedly totalling $US4tr, although this would be delivered over several years and financed more by increased taxes than debt. At the same time, US households saved at a rapid pace last year as lockdowns stopped people from spending and saved some earlier financial support. These “excess” household savings – as proxied by the difference between household net cash flow in 2020 versus 2019 – are about 8% of GDP.

Former policy-makers worry about how easy policy led to the “great inflation” of the 1960s and 1970s. Concern about stimulus stoking inflation is influenced by the memory of the 1960s and 1970s, when the US recorded the highest sustained inflation rates outside of war. That policy mistake has been widely attributed by Fed researchers to a combination of: (1) policy-makers placing a greater weight on stabilising output and unemployment rather than inflation, which is understandable given their views would have been shaped by the policy failure of the Great Depression; (2) the Fed misreading the Phillips Curve trade-off between low unemployment and higher inflation by underestimating the non-accelerating inflationary rate of unemployment (NAIRU) and overlooking shifts in the relationship driven by higher inflation expectations; (3) the Fed accommodating expansionary fiscal policy; and (4) the exacerbating effect of the oil price shocks of the 1970s.

In judging the risks to inflation, the Phillips curve suggests inflation can be driven higher by either an overheating economy and/or higher expected inflation. In a simple representation of inflation, the expectations-augmented Phillips Curve specifies that inflation = expected inflation + α*(unemployment – NAIRU). In this framework, higher inflation can reflect either an overheating economy, where the unemployment rate falls below the NAIRU, and/or higher expected inflation.

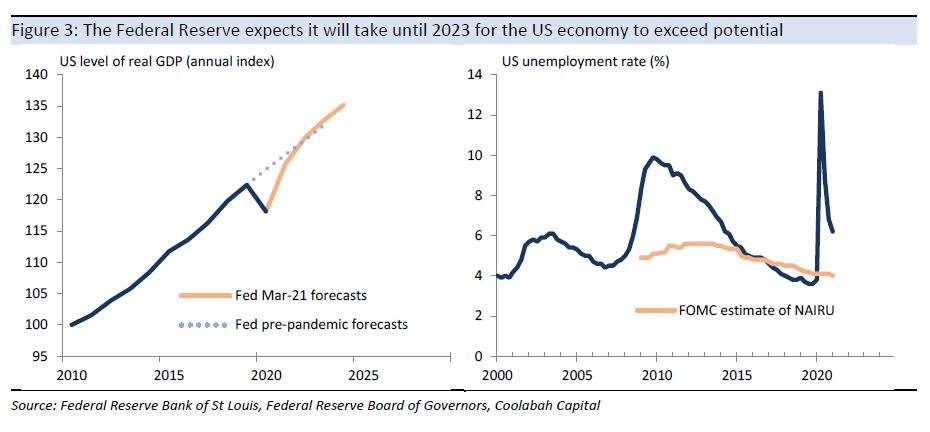

Overheating seems unlikely in the short term. The pandemic opened-up substantial slack in the US economy, although output has rebounded more quickly than first anticipated, with unemployment falling at a faster rate than initially forecast. On its current outlook – where the fiscal stimulus peaks in 2021 – the Federal Reserve expects US real GDP to return to its pre-pandemic trajectory in 2022, with output modestly above the pre-pandemic path in 2023. The labour market is expected to follow a similar path, with unemployment taking until 2023 to fall below the Federal Open Market Committee’s 4% estimate of the NAIRU.

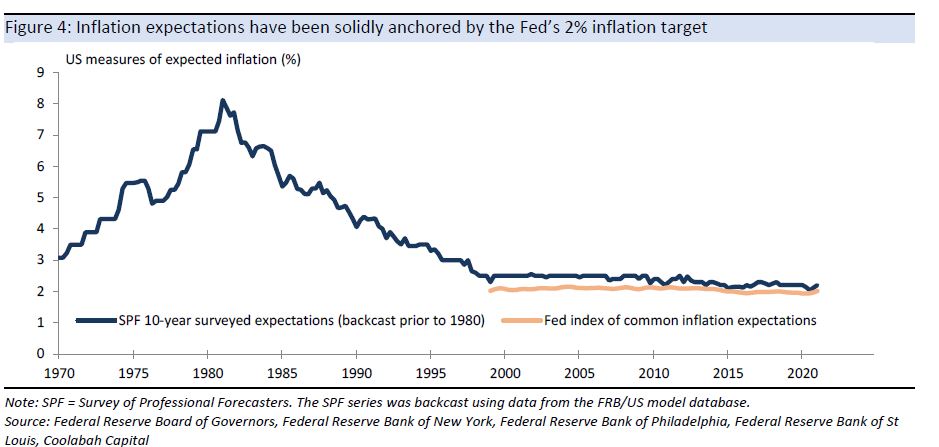

There is less certainty about expected inflation. Historically, expected inflation was heavily influenced by actual headline inflation, but over the past couple of decades it has been solidly anchored by the Fed’s 2% target for inflation. This hard-won credibility – where the Fed used double-digit interest rates to bring inflation under control during the 1980s – is clear from the Fed’s summary index of common inflation expectations, which has held closely to the 2% target during the pandemic, rebounding early this year to 2.0% from a low of 1.9% at the worst point of the outbreak last year. If a crack appeared in the Fed’s credibility and expected inflation started to respond to higher headline inflation – which should spike on the recovery in oil prices, pandemic costs related to supply chain disruptions and the reversal of price cuts made during lockdowns – this would feed into higher ongoing inflation.

There is less certainty about expected inflation. Historically, expected inflation was heavily influenced by actual headline inflation, but over the past couple of decades it has been solidly anchored by the Fed’s 2% target for inflation. This hard-won credibility – where the Fed used double-digit interest rates to bring inflation under control during the 1980s – is clear from the Fed’s summary index of common inflation expectations, which has held closely to the 2% target during the pandemic, rebounding early this year to 2.0% from a low of 1.9% at the worst point of the outbreak last year. If a crack appeared in the Fed’s credibility and expected inflation started to respond to higher headline inflation – which should spike on the recovery in oil prices, pandemic costs related to supply chain disruptions and the reversal of price cuts made during lockdowns – this would feed into higher ongoing inflation.

Inflation expectations are currently well-anchored, but history shows sudden shifts can occur. Although it is very encouraging that the Fed’s measure of inflation expectations and bond market expectations appear solidly anchored by the 2% inflation target, abrupt shifts in inflation expectations have occurred in the past. As MIT professor and former IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard argued, “ … The history of the Phillips curve is one of shifts, largely due to the adjustment of expectations of inflation to actual inflation. True, expectations have been extremely sticky for a long time, apparently not reacting to movements in actual inflation. But, with such overheating, expectations might well de-anchor. If they do, the increase in inflation could be much stronger. …”.

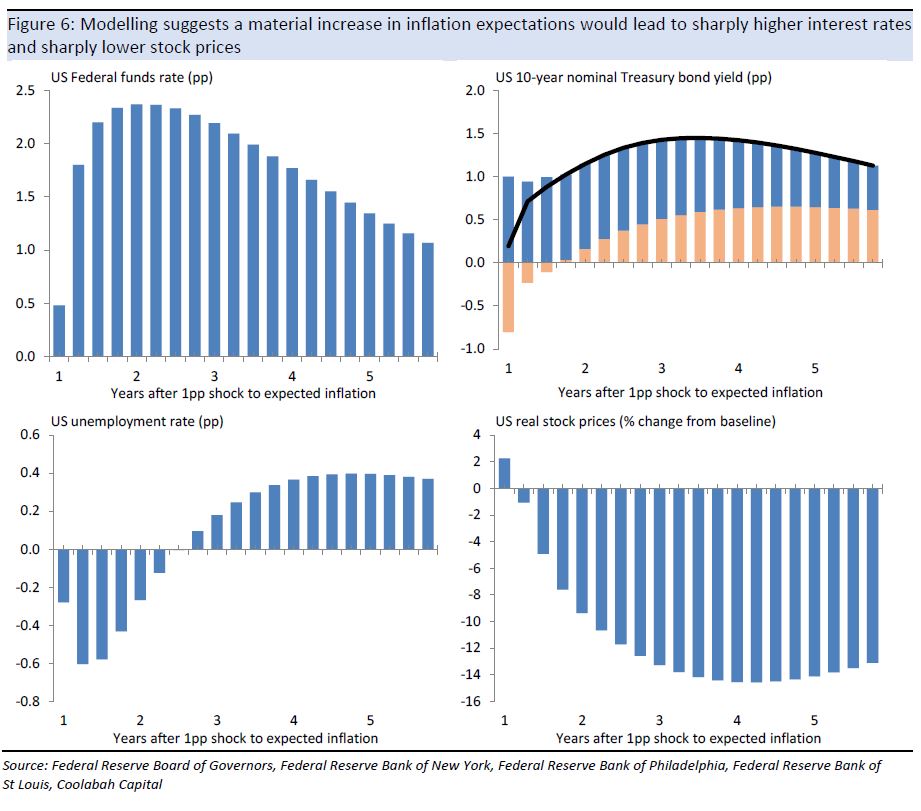

Analysis suggests that a material increase in expected inflation would lead to sharply higher interest rates and a large fall in stock prices. To gauge the potential effect of a rise in inflation expectations we estimated the effect of a 1pp increase in expectations on US financial markets and the economy using a VAR model. A 1pp increase represents a large shock considering that the standard deviation of expected inflation is 0.6pp over recent decades (we used the Survey of Professional Forecasters’ 10-year expectations series because the Fed’s summary index has a relatively short history). The results suggest that a sudden increase in inflation expectations leads to:

- tighter monetary policy to bring inflation under control, with the Fed funds rate increasing by almost 2.5pp;

- a sharply higher 10-year bond yield, increasing by almost 1.5pp, reflecting persistence in the shock to inflation expectations and an eventual increase in real yields given tighter monetary policy;

- lower unemployment in the near term, indicating that higher inflation expectations are normally associated with an improving labour market, but higher unemployment over the medium term as the Fed tightens policy to control inflation; and

- sharply lower stock prices, which are down about 15% in real terms.

Kieran is responsible for macroeconomic research and investment strategy at Coolabah and contributes to Livewire regularly. You can view his recent insights and follow future contributions here.