This is an article published on Livewire Markets recently by Kai Lin, Head of Data Science, and Christopher Joye, Portfolio Manager, Coolabah Capital Investments.

Coolabah has attempted to forecast both the advent of “herd immunity” in Australia and when governments will be comfortable opening-up our borders to both inflows and outflows of vaccinated human capital, subject to strict testing protocols at arrival and departure ports.

Leveraging off the extant empirical vaccination trajectories of comparable countries around the world, Coolabah projects that more than 90% of Australia’s adult population should be vaccinated sometime between January and February 2022. This marries up with a potential Federal election in March 2022, following which governments would start opening-up the country via travel bubbles with select nations in mid 2022.

This has significant ramifications for policymakers given that open borders are likely to eventually precipitate a substantial positive labour supply shock via much higher population growth, which should ultimately more than offset the negative labour supply shock that resulted from the combination of closed borders and around 334,000 foreign workers fleeing Australia after the advent of the COVID-19 crisis. Any increase in wage growth in 2021 and 2022 could be counterbalanced by this positive labour supply shock.

Introduction

Outside of the outbreak of war between China and the US, perhaps the single-biggest event risk that policymakers, and the RBA specifically, should be thinking about right now is when Australia’s iron-clad borders will finally open-up to new human capital flows in and out of the country. This is certainly something that we have been trying to turn our minds to a little more thoroughly of late.

Once the borders open, Australia is likely to experience a large skilled migration and general labour supply shock, which could over time put material downward pressure on wages and inflation. This will, however, be preceded by a temporary tightening of the labour market as the 334,000 jobs held by “non-residents” prior to the COVID crisis have been shifting to locals or residents.

As our Chief Macro Strategist, Kieran Davies, has explained, these jobs were not previously in the official employment data (because they were held by non-residents), and as they do magically shift into the official statistics when they are allocated to locals/residents, they have the potential to temporarily reduce the unemployment rate by more than two percentage points. This is almost certainly one key driver of the radical recent reduction in the jobless rate from 7.4% to 5.1%, and also the surge in the advertised vacancy rates.

Accordingly, policymakers are going to have to traverse the current negative labour supply shock juxtaposed against the spectre of a positive labour supply shock as skilled migration and population growth ramp-up in the years ahead.

The existential question is, therefore, when will the borders open back-up? To try to forecast this somewhat more rigorously, we have made a few assumptions:

- We think the Federal Government will not open any borders until after the next election, which would be optimally timed for either March or May 2022;

- We assume that the Federal Government will not hold the next election until all Australians who want to be vaccinated have obtained their jabs, which begs the question as to when this will likely be;

- We assume that a lower-bound on this minimum acceptable vaccination rate to re-open the borders will be equivalent to the penetration necessary to be confident of the community capturing robust herd immunity; and

- Subject to these decision-making rules being satisfied, we believe that following the election the Federal Government will look to slowly allow fully-vaccinated Australians to start travelling overseas, and vaccinated foreigners to come to Australia, conditional on strict COVID testing of departures and arrivals, and home quarantine if and when required. This may initially be achieved through establishing a number of travel bubbles (eg, with New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, etc), which could be rapidly expanded over time with other destinations that.

As noted above, opening our borders requires herd immunity to COVID-19, which means that a sufficient portion of the population have immunity either via recent infection or through effective vaccination that is approved by the Australian government.

The exact coverage required for herd immunity is not yet known, because it depends on factors such as vaccine efficacy, reinfection rates, and so on. The research consensus estimate is around 60% to 90% of the total population. The upper-end of this range may not be achievable without extending vaccine eligibility to children, and will likely require strong government incentives to overcome any vaccine hesitancy.

For Australia, we believe that once around 70% of the total population (or more than 90% of the adult population) have been fully vaccinated, the government will consider opening the borders subject to the various protections outlined above.

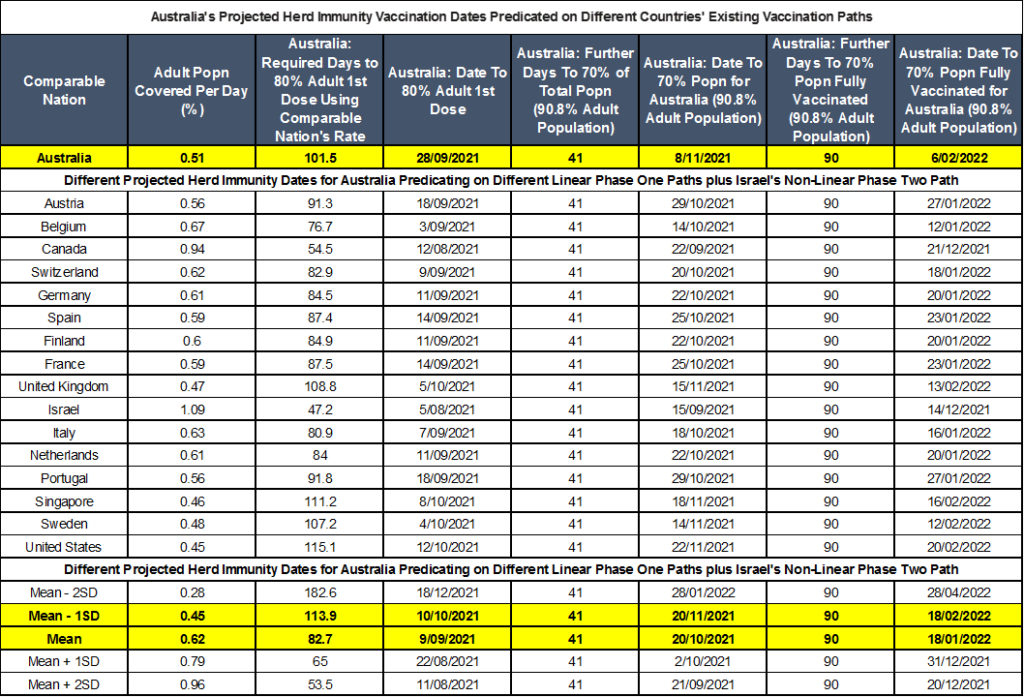

The technical challenge is therefore figuring out when Australia will likely have vaccinated 70% of its total population (or over 90% of all adults). Based on our research, we project that 70% of total population (or 90.8% of adults) will be fully vaccinated by January or February 2022. This potentially opens the door to a March election and the prospect of borders starting to open in mid 2022.

Projection Methodology

Our projections are developed using a three phase process. Phase one involves estimating the time it takes for 80% of the adult population to have their initial jab, excluding children who are generally not eligible for vaccination. Note that 80% of the adult population is equivalent to 61.8% of Australia’s total population.

We do this harnessing the empirically linear path of comparable nations’ actual vaccination trajectories, where it appears that the vaccination campaign has been logistically established and is running at a mature capacity.

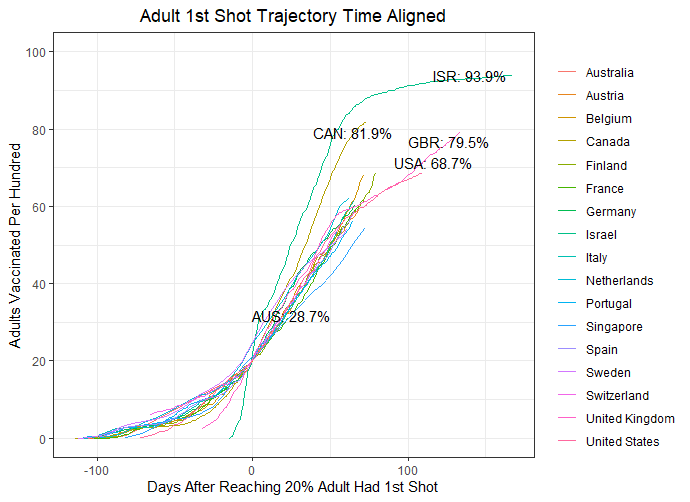

Australia is currently in this linear trajectory, having vaccinated 28.7% of its adult population at a rate of about 0.51% of all adults per day. Comparable nations vaccinate an average of 0.62% of their adult population per day (or 0.45% per day at a one standard deviation slower pace than the average nation).

The global vaccination coverage is shown in the first chart below, illustrating high-income nations comparable to Australia and the percentage of their total population that has had at least one vaccine dose. The four nations clearly ahead are Israel (early leader, but since slowed dramatically), Canada (late but very rapid rise), the UK and the US. Although Australia is the laggard, it does appear our trajectory has just time-shifted: that is, it started late, but with no indication of it being any slower than the others once it has ramped up.*

In phase two of the process, we estimate the non-linear deceleration in vaccination rates from 80% of adults having had their first shot to the idealised 90.8% of adults (equating to 70% of the total population) having had an initial shot, assuming children are not eligible for vaccination.

We do this by predicating Australia’s vaccination path on the trajectory experienced by Israel, which has been demonstrably ahead of the rest of the world time-wise. Based on the evidence from Israel and others, there is some clear vaccine hesitancy once you vaccinate 80% of adults. This is highlighted by the significant deceleration in the pace of new vaccinations, as the chart shows . (Note that Israel is the only medium-to-large nation that has hit this saturation part of their trajectory.)

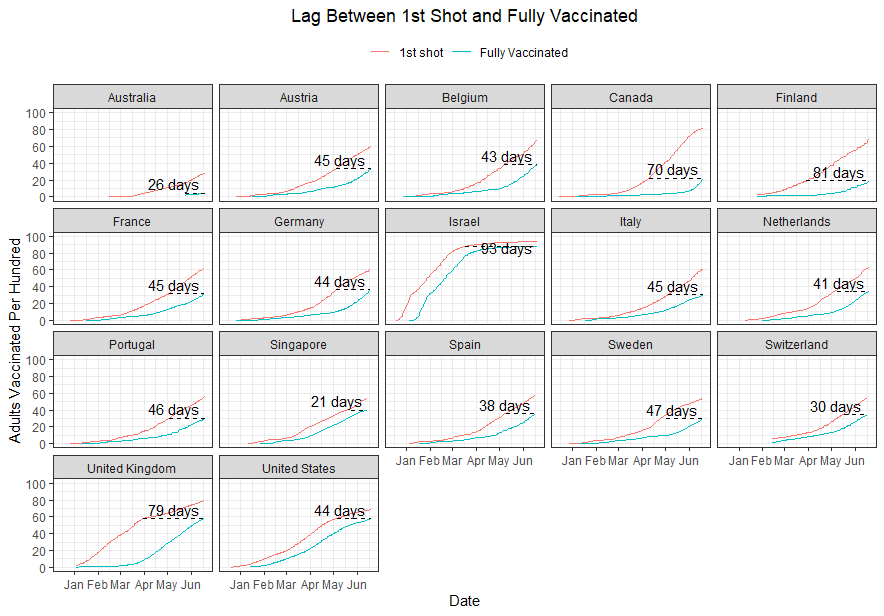

Finally, in phase three of the projection we calibrate the time lag between getting the first shot and being fully vaccinated based off the observed intervals between the Pfizer and AstraZeneca shots, adopting the latter’s 90 day lag for conservatism’s sake.

While the dramatic slowdown in Israel’s vaccination coverage might appear worrying, it is actually more benign given that children under 16 years of age are not eligible for vaccination in Israel until June 2021. The minimum age for vaccine eligibility differs slightly across the world, either due to low queue priority or lack of safety approvals. For this analysis, we assumed 18 years of age was the cut-off.

The chart below shows the rate of coverage for adults’ first shot. Observe that Israel started slowing down around the 80% adult mark, as did Canada, though the UK looks poised to power through.

This insight informs phase one of our projection. This is based on the observation that the daily increase in the adult population covered by at least one shot of vaccine increases linearly (ie, steadily) when the adult coverage is between roughly 20% and 80% range (ie, after logistics are set up, and before saturation of the adults that are willing vaccine takers). Note that we use the adult population in order to remove population-age distribution differences across nations, allowing their trajectories to line up well, as shown in the plot below.

Results

Australia currently has 28.7% of adults covered by at least one shot. To get to 80% adult coverage (equivalent to 61.8% of total population coverage), Coolabah estimates that it should take 83 days based on the average of the days taken by these plotted comparable countries, or 114 days if Australia is one standard deviation slower. That forms the basis of Coolabah’s projection that Australia will likely obtain 80% adult vaccination coverage some time between early September and mid October 2021, depending on the assumptions one makes.

In a similar fashion to the ‘substitute country’ methodology Coolabah developed in its COVID-19 case forecasting models, we can substitute in the vaccination trajectory of other countries such as the UK, which took 108.8 days from where Australia currently is to the target 80% adult coverage. Our final table below allows the analyst to select any individual country’s trajectory for the linear part of the phase one growth process.

Going beyond 80% of adults having had the first shot, Australia will likely experience the aforementioned deceleration in vaccination rates due to residual hesitancy. The only medium to large country having gone past this adult coverage is Israel. It took Israel 41 days to go from 80% adult to 90.8% adult coverage (the adult coverage required to achieve 70% total population coverage in Australia). We will add this to the above estimate of days to 80% adult coverage, to get projected time to 70% of the total population (90.8% of adults) getting their first shot.

Phase three of the projection is the time between getting the first shot and becoming fully vaccinated. This lag is plotted below for the comparable countries. The lags range between 1 and 3 months. However, note that as the population gets saturated, the lag blows out (eg, for Israel, to 90+ days). Of course, different vaccines have different time lags between the first and second shots: whereas Pfizer is roughly 1 month, AstraZeneca is 3 months. We remain on the conservative side of this range, and assume a lag of 90 days.

In summary, Coolabah’s research estimates the duration of the three different components of Australia’s journey to reaching herd immunity based on empirically observed experiences around the rest of the world. The first phase one roll-out takes about 114 days to ensuring 80% of the adult population gets their initial dose. The slower phase two process takes another 41 days to reach 90.8% of adult population (or equivalently 70% of total population). The final phase three process requires 90 days to secure 70% of total population having been fully vaccinated. This implies about 245 days from the time of writing, and suggests that Australia should get to herd immunity somewhere between mid January 2022 and late February 2022. The table below shows Coolabah’s herd immunity forecasts for Australia predicating off a range of different empirical vaccination trajectories.

*The data is sourced from Our World In Data, citation: Mathieu, E., Ritchie, H., Ortiz-Ospina, E. et al. A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations. Nat Hum Behav (2021). Note there is a gap in the data for Australia during which no data for person level vaccination was available. We have linearly interpolated between these dates. This dataset only contains people vaccinated, and does not distinguish between adult or children. We assumed that all people vaccinated thus far are adults because vaccine eligibility for children is very limited around the world.